First Chapter, Section 6

Western Mindfulness: Expanding Scientifically on Ellen Langer’s Concept

Tools of Mindfulness

- Creation of New Categories

- Openness to New Information

- Awareness of More Than One Perspective

In her book Mindfulness, social psychologist Professor Ellen Langer defines mindfulness as the study of the link between the mind and human behaviors. Langer’s approach to mindfulness is distinct from Eastern meditation practices. Her research initially focused on mindlessness, which she describes as habitual, unthinking actions that can lead to significant problems in daily life. She demonstrates how fixed perspectives can cause us to overlook things that are right in front of us and how this oversight incurs substantial costs.

Mindlessness: A Cognitive Trap

Mindlessness occurs when we rely too heavily on mental categories and distinctions formed by previous experiences. Over time, these categories gain momentum and become difficult to overcome. We construct our realities based on these categories, ultimately becoming victims of our own cognitive frameworks.

For example, we might assume that everything we read in newspapers, including advertising, is written with good intentions, is truthful, and can never be incorrect. This tendency to accept information uncritically can lead to a distorted understanding of reality. When we join a group, follow a teacher, or practice a discipline, this uncritical acceptance often intensifies. However, the lessons from books, maps, and beliefs are merely signposts—indicators of a deeper truth that must be discovered individually.

Automatic Behavior and Single Point of View

Automatic behavior is another aspect of mindlessness. Psychologists suggest that many cognitive behaviors, such as reading and writing, can be performed automatically and without conscious intention. Acting from a single point of view is another facet of mindlessness. Often, we behave as though there is only one set of rules to follow. For instance, when cooking and following recipes, we might adhere to the instructions rigidly, fearing any deviation. This contrasts sharply with cooking mindfully, where creativity and experimentation are encouraged.

Mindlessness in Everyday Life

Mindlessness can sometimes be amusing, as illustrated by the following anecdote: A young or newly married woman preparing a roast chopped a small piece off before placing it in the pan. When asked why, she replied that her mother always did it that way. Curious, she asked her mother, who gave the same response. Eventually, the grandmother revealed the practical reason: “Because that’s the only way it would fit in my pot.” This story highlights how mindless repetition of behaviors can persist across generations without questioning their original purpose.

Origins of Mindlessness

Mindlessness stems from various factors, including repetition, early cognitive commitment, belief in finite resources, the concept of linear time, schooling for results, and the profound impact of context. Context can significantly influence our perceptions and behaviors, as demonstrated by the story of Eliza Doolittle in Shaw’s Pygmalion (also known from the film My Fair Lady). Eliza transforms from a shabby flower girl to a celebrated beauty, not through intrinsic change, but by altering her context—her voice, language, wardrobe, and habits. This transformation underscores the power of context in shaping self-perception and behavior.

Achieving Mindfulness Through Increased Focus

Increased focus results in mindfulness, characterized by:

- Development of New Categories: Creating new ways to categorize and understand experiences.

- Receptivity to New Information: Being open to learning and integrating new information.

- Awareness of More Than One Perspective: Recognizing and considering multiple viewpoints.

These attributes stem from heightened attentiveness and conscious engagement with one’s environment.

Scientific Expansion on Langer’s Concept

Neuroscientific Perspective

Neuroscientific research supports the concept of mindfulness by demonstrating how increased attentiveness can alter brain function. Studies using functional MRI (fMRI) have shown that mindfulness practices can enhance activity in the prefrontal cortex, the brain region associated with attention, planning, and decision-making. This increased neural activity correlates with improved cognitive flexibility, allowing individuals to create new categories and remain open to new information.

Cognitive Psychology

From a cognitive psychology standpoint, mindfulness can be understood through the lens of cognitive restructuring. Cognitive restructuring involves identifying and challenging existing cognitive distortions and creating new, healthier ways of thinking. This process aligns with Langer’s emphasis on developing new categories and being open to new information.

Behavioral Economics

Behavioral economics provides another angle, illustrating how mindfulness can counteract biases and heuristics that lead to suboptimal decision-making. By fostering awareness of multiple perspectives, mindfulness helps individuals avoid the pitfalls of anchoring, confirmation bias, and other cognitive biases, leading to more rational and informed decisions.

Educational Psychology

In educational psychology, Langer’s concept of mindfulness can enhance learning outcomes. By encouraging students to approach problems with an open mind and consider various perspectives, educators can foster a more adaptive and resilient mindset. This approach aligns with constructivist theories of learning, which emphasize the active role of learners in constructing their understanding.

Therapeutic Applications

Mindfulness-based therapeutic techniques, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), have been shown to be effective in treating conditions like anxiety, depression, and chronic pain. These therapies incorporate practices that increase attentiveness and foster openness to new information, echoing Langer’s findings on the benefits of mindfulness.

Practical Applications

Retraining the Mind

Developing a youthful and/or naïve frame of mind can effectively retrain your mind. This book will guide you in building child-like observation abilities, listening skills, learning skills, and connections (relatedness). These practices can help you break free from mindlessness and embrace a more mindful approach to life.

Externalizing Problems

Externalizing is a therapeutic strategy that encourages individuals to view oppressive conditions as distinct entities outside themselves. This method allows individuals to observe their harmful behavior more objectively and is supported by spiritual pathways, meditation, and practices like yoga.

Spiritual Meditation

Mastering spiritual meditation can provide insights into yourself and how your mind operates. This practice helps you identify and dismantle negative patterns, achieving mental stability and concentration. It is freeing and illuminating, allowing the release of negativity and fostering enlightenment.

Living a Path with Heart

A path with a heart includes our unique gifts and creativity. Whether writing books, building structures, serving others, or playing music, the creations of our lives must be grounded in our hearts. Love is the source of all energy to create and connect. Acting without a connection to the heart can lead to a life that feels dried up, meaningless, or barren.

Harmonious Development of the Mind

An enrichment of personality and a strengthening of character inevitably follow since the three basic elements of the mind—intellect, feeling, and will—develop harmoniously. By integrating mindfulness, intrinsic motivations, and a positive perspective, you can foster a fulfilling and creative life, transforming challenges into opportunities for growth and enlightenment.

Consciousness

|

|---|

Consciousness as an Information Processing System: A Scientific Exploration

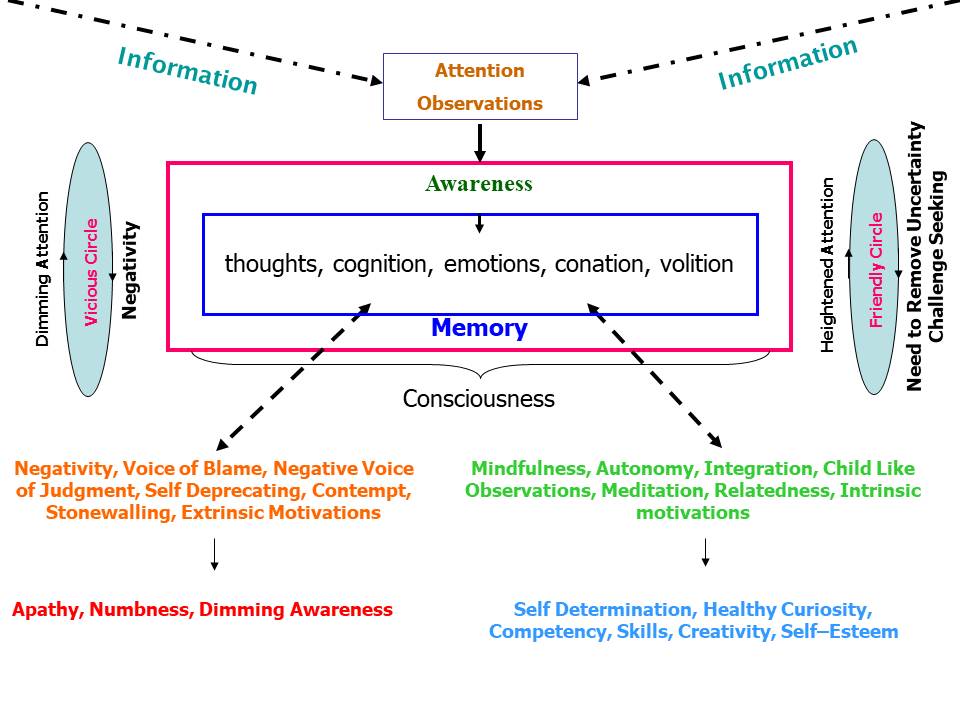

Consciousness as a Productive Factory

As previously explained, consciousness functions much like a productive factory or, more precisely, an information processing system. When certain components are supplied, and the equipment is set up to generate a specific end, the output will be that desired outcome. This analogy highlights the critical role of inputs and machinery in shaping our conscious experience.

Key Components: Input and Machinery

The input (observation and attention) and the machinery (awareness) are the two most significant parts of this factory. A shift in perception is akin to preventing improper materials from entering your manufacturing process. By refining these inputs and adjusting the machinery, we can enhance the quality of the output, i.e., our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

Modifying the Machinery: Creating New Brain Regions and Patterns

Creating New Regions in the Brain

Modifying the machinery involves creating new regions in the brain and establishing new patterns of intuition. Neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections, plays a crucial role here. Neuroplasticity is fundamental for learning new skills, adapting to new experiences, and recovering from injuries. By engaging in specific activities that promote neuroplasticity, we can enhance our cognitive and emotional capabilities.

Steps to Enhance Consciousness

-

Attentiveness

- Scientific Insight: Attentiveness is linked to the brain’s prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for focus, decision-making, and executive functions. Practices like mindfulness meditation have been shown to increase the density of gray matter in the prefrontal cortex, enhancing attentional control.

- Practical Application: Mindfulness exercises, such as focused breathing and body scan meditations, can improve attentional control and reduce mind-wandering.

-

Openness to New Information with Childlike Insights

- Scientific Insight: Openness to new information is associated with cognitive flexibility, a function of the prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex. This flexibility allows individuals to adapt their thinking in response to new and unexpected conditions.

- Practical Application: Engage in activities that challenge existing beliefs and encourage novelty, such as learning a new language or playing an unfamiliar musical instrument.

-

Awareness of Another Point of View

- Scientific Insight: Empathy and perspective-taking are functions of the brain’s mirror neuron system and the temporoparietal junction. These regions enable us to understand and predict the thoughts and feelings of others.

- Practical Application: Practice active listening and empathy exercises, such as role-playing scenarios where you must argue from another person’s perspective.

-

Self-Sufficiency

- Scientific Insight: Self-sufficiency is tied to the brain’s default mode network, which is involved in self-referential thought processes. Building self-sufficiency enhances self-regulation and resilience.

- Practical Application: Foster independence by setting personal goals and working towards them without external validation. Journaling and self-reflection can also enhance self-awareness and autonomy.

-

Spending Time with Trusted and Respected Individuals

- Scientific Insight: Positive social interactions stimulate the release of oxytocin, a hormone that promotes bonding and trust. Social support is crucial for mental health and cognitive functioning.

- Practical Application: Cultivate meaningful relationships by spending quality time with friends and family. Participate in group activities that foster a sense of community and mutual respect.

The Neuroscience of Autonomy and Meaningful Connections

Desire for Autonomy

- Scientific Insight: Autonomy is closely linked to intrinsic motivation, which is regulated by the brain’s reward system, including the ventral striatum and the prefrontal cortex. When individuals have control over their actions, they experience greater motivation and satisfaction.

- Practical Application: Encourage self-directed learning and decision-making in everyday activities. Pursue hobbies and projects that align with your interests and values.

Development of Meaningful Connections

- Scientific Insight: Meaningful connections activate the brain’s social networks, including the amygdala, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and posterior cingulate cortex. These regions are involved in processing social information and emotional bonding.

- Practical Application: Engage in deep, meaningful conversations and activities that promote mutual understanding and shared experiences. Volunteering and community service can also strengthen social bonds.

The analogy of consciousness as a productive factory underscores the importance of inputs (observation and attention) and machinery (awareness) in shaping our conscious experience. By refining these elements, we can enhance our cognitive and emotional well-being. Engaging in practices that promote neuroplasticity, attentiveness, openness to new information, empathy, self-sufficiency, and meaningful connections can lead to the development of new brain regions and patterns of intuition. These changes foster autonomy and the creation of a fulfilling, connected life. Through scientific understanding and practical application, we can transform our consciousness and achieve greater personal and social fulfillment.