Observation Skills

A beautiful thing never gives so much pain as does failing to hear and see it. MICHELANGELO

Take a look at these two quotes:

Art does not render the visible; it makes the visible. PAUL KLEE

I love Paris in the

the springtime

COLE PORTER

Read the Cole Porter quote several times. Did you? Anything wrong with it? No?

Look at it again below:

I love Paris in the springtime.

Do you see it now? Why did you miss it the first, second, or third time?

Enhancing Observation Skills: A Path to Better Understanding and Creativity

The Challenge of Familiarity

We are often so familiar with expressions and phrases that we fail to truly “see” them. This mindless observation is a common occurrence, especially with our most developed sense—vision.

Many of us would read this line multiple times without noticing the repetition of “the.” This happens because our brains rely on familiar patterns, causing us to overlook details we think we already know. This illustrates how critical it is to develop observation skills to truly understand and appreciate the world around us.

Developing Observation Skills

The Importance of Mindful Observation

To remove the unknown and enhance motivation, we must cultivate the ability to observe mindfully. This involves making distinctions (seeing how things differ) and drawing analogies (seeing how things are similar). Both approaches are essential for creating new categories and shifting contexts, which are foundational to mindfulness and creativity.

Analogical Thinking and Creativity

Analogical thinking, or the ability to see relationships between seemingly unrelated concepts, is a key component of intelligence and creativity. For instance, the Miller Analogies Test, used in graduate admissions, measures this skill through questions like:

“Lion is to Pride as Horse is to (circle one) Vanity Herd Corral.”

Analogical thinking involves applying concepts learned in one context to another. This mental operation is inherently mindful. Architects, for example, who can see similarities between a hospital and a hotel, can design more responsive and innovative solutions. This ability to draw analogies and mix metaphors intentionally can spark new insights and deeper understanding.

The Role of Context and Mindfulness

Contextual Perception

Our perception is significantly influenced by context. The famous analogy of the Persian rug, where colors that seem different are actually the same when viewed from another angle, demonstrates how context can alter our perception. This concept is essential in problem-solving and creativity, as it encourages us to look at problems from different perspectives to uncover hidden connections.

Historical Examples of Observational Skills

Archimedes’ “Eureka!” moment is a classic example of keen observation. He discovered the principle of water displacement while noticing how his bathwater level rose as he entered the tub. This insight allowed him to determine the volume of an irregularly shaped crown without damaging it. Similarly, Richard James’ observation of a spring “walking” led to the invention of the Slinky, a toy that has fascinated generations.

The Impact of Routine and Predictability

The Comfort and Limitation of Routine

While routines provide predictability and comfort, they can also hinder our ability to notice new opportunities and changes. Fixed ways of seeing and expecting can prevent us from recognizing important details or trends. Breaking free from routine requires deliberate efforts to challenge our assumptions and seek out new experiences.

Paradigm Shifting and the “Aha!” Moment

Paradigm shifts, or “Aha!” moments, occur when we change our perception and see a situation in a completely new way. These shifts often result from questioning our initial assumptions and being open to alternative perspectives. Dr. Stephen Covey’s concept of paradigm shifting emphasizes the transformative power of changing how we see the world.

The Role of Art and Creativity

Art as a Tool for Observation

Art provides a unique lens through which we can enhance our observation skills. Paul Klee’s statement, “Art does not render the visible; it makes the visible,” suggests that art encourages us to see beyond the surface and explore deeper meanings. Engaging with art can train our brains to notice subtle details and appreciate different perspectives.

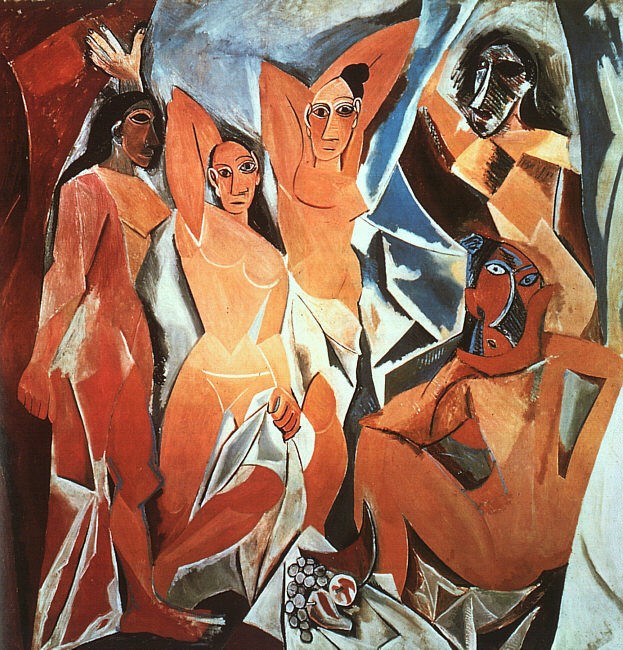

Picasso’s Perspective on Reality

Picasso’s response to how women “really look” highlights the subjective nature of perception. His observation that a photograph does not capture the essence of a person challenges us to consider how our perceptions are shaped by context and representation. This perspective encourages us to question our assumptions and explore alternative ways of seeing the world.

Developing observation skills is crucial for enhancing perception, creativity, and problem-solving. By cultivating mindful observation, embracing analogical thinking, and being aware of contextual influences, we can improve our ability to see the world clearly and make meaningful connections. Historical examples and artistic perspectives demonstrate the power of keen observation in driving innovation and understanding. Through deliberate practice and a willingness to challenge our assumptions, we can remove the unknown and unlock our full potential.

|

| Les demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), oil on canvas (96 x 92). Picasso’s early creative breakthrough. |