First Chapter, Section 4

The Essence of Learning: Embracing Life’s Lessons with Mindfulness

John Holt on Learning

John Holt once said: “We learn something from everything we do and everything that happens to us or is done to us.” This profound insight underscores the idea that learning is a continuous process shaped by every experience we encounter. What we see, notice, and eventually learn in life from our friends and family makes us more informed or more ignorant, sometimes smarter or sometimes less so, but we always learn something. The quality of our learning is largely determined by our internal experience and, more importantly, how we feel about it.

The Role of Emotion in Learning

Our emotional response to an experience significantly influences what we learn from it. Encounters that are uninteresting or deemed unimportant are unlikely to impart useful knowledge. Even more crucially, we gain little from coercive encounters, particularly those involving bribery, intimidation, harassment, or deception. These negative experiences tend to inhibit meaningful learning and growth.

Living on Autopilot

Living life on autopilot can have unfavorable consequences. To paraphrase John Holt, individuals who watch television on autopilot learn that the personalities they see on TV are, in every sense, superior to them. They witness TV celebrities who appear younger, sexier, brighter, stronger, quicker, braver, wealthier, happier, more successful, and more respected. This passive consumption of media can lead to feelings of inadequacy and a distorted perception of reality.

Mindful Engagement

In contrast, mindful engagement with life fosters deeper learning and personal growth. Zen Master Roshi Philip Kapleau, in his excellent book Awakening to Zen, emphasizes the importance of experiential awareness. He recounts the teaching of Ummon, a great Zen master of the T’ang period in China, who said to his assembly of monks, “The world is vast and wide. Why do you put on your seven-piece robe at the sound of the bell?”

Ummon’s message is clear: Experience for yourself this limitless universe—touch it, taste it, feel it, be it. Thoroughly savor it. Don’t speculate about life and the world. Live it! This is true freedom—religious freedom and spiritual freedom. Ummon is urging us to fully engage with our roles and responsibilities. If you are a monk, put on your robes when the bell rings announcing the morning service. If you are an office worker, go to the office. If you are a husband, kiss your wife and children and drive to work. If you are a student, go to school. If you are a school teacher, open the door and ring the bell. Don’t drag your feet and complain, “Why should I?” Awakening brings the experiential awareness that the world is an unfathomable void, yet every single thing embraces this immense cosmos.

The Importance of Mindful Learning

Mindful learning involves being fully present in each moment, actively engaging with your environment and experiences. This approach not only enhances the quality of your learning but also enriches your life. By paying attention to your experiences and reflecting on them, you can derive deeper insights and understanding.

Emotional Intelligence in Learning

Emotional intelligence plays a crucial role in mindful learning. By being aware of your emotions and how they influence your perceptions, you can better understand and manage your reactions. This awareness allows you to approach each learning opportunity with an open mind and a positive attitude, maximizing the potential for personal growth.

Embracing the Vastness of Life

The teachings of Zen emphasize the importance of embracing the vastness of life and being fully present in each moment. This perspective encourages us to see the world not as a series of mundane tasks but as a rich tapestry of experiences, each offering valuable lessons. By approaching life with curiosity and openness, we can transform ordinary moments into opportunities for profound learning.

Conclusion

Learning is an ongoing journey shaped by every experience we encounter. By embracing mindful engagement and emotional intelligence, we can enhance the quality of our learning and personal growth. The teachings of Zen remind us to be fully present in each moment, experiencing life in its entirety. This approach fosters a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world around us, enabling us to live more fulfilling and meaningful lives. Through mindful learning, we can transform our everyday experiences into opportunities for growth and enlightenment.

Human Consciousness

|

|---|

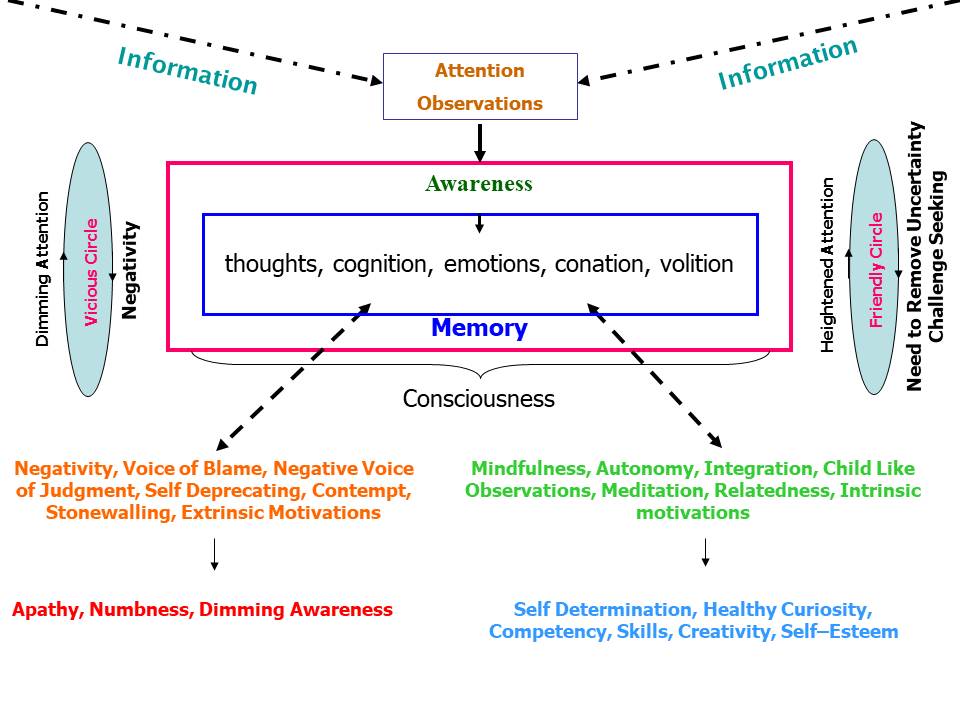

The image above represents the central concept of the book, focusing on how human awareness functions similar to a factory. Here’s a detailed breakdown of the elements within the image:

-

Information Input: Information enters from the environment through attention and observations. This is analogous to raw ingredients entering a factory.

-

Attention and Observations: These are critical inputs that feed into the awareness process. How we pay attention to and observe our surroundings significantly impacts what we process internally.

-

Awareness: This is the central processing unit, much like machinery in a factory. It processes thoughts, cognition, emotions, conation (intention), and volition (will). Awareness takes the raw input (information) and processes it into memory.

-

Memory: The processed output that influences consciousness. Memory feeds back into awareness, creating a continuous loop of information processing.

-

Consciousness: The state of being aware of and responsive to one’s surroundings. It is influenced by both the immediate input and the accumulated memory.

-

Friendly or Virtuous Circle: Represents a positive feedback loop facilitated by heightened attention and the need to remove uncertainty and seek challenges. This loop is driven by:

- Mindfulness

- Autonomy

- Integration

- Childlike observations

- Meditation

- Relatedness

- Intrinsic motivations

-

Self-Determination: Outcomes of the friendly circle include:

- Healthy curiosity

- Competency

- Skills

- Creativity

- Self-esteem

-

Vicious Circle: Represents a negative feedback loop caused by dimming attention and negativity. It includes:

- Negativity

- Voice of blame

- Negative voice of judgment

- Self-deprecation

- Contempt

- Stonewalling

- Extrinsic motivations

-

Apathy and Numbness: Outcomes of the vicious circle, leading to dimmed awareness and a reduction in positive processing.

The image draws an analogy between human awareness and a chocolate factory to explain how we process information and form our perceptions and memories.

Human Awareness as a Factory

-

Inputs (Observation and Attention): Like ingredients in a factory, the quality and nature of the inputs determine the final product. When we observe our environment mindfully and pay attention with a positive outlook, we feed our mental processes with high-quality “ingredients.”

-

Processing Unit (Awareness): Awareness is the machinery that processes inputs into meaningful thoughts, emotions, and memories. Just like factory machinery needs to be calibrated correctly to produce good quality outcome, our awareness needs to be attuned to process information effectively. This involves mindfulness and a conscious effort to maintain a positive and open mindset.

-

Outputs (Memory and Consciousness): The processed outputs in a chocolate factory are the finished products—chocolates. Similarly, the outputs of our mental processing are our memories and our conscious awareness. These outputs are crucial as they shape how we perceive the world and react to future inputs.

Positive vs. Negative Feedback Loops

-

Friendly or Virtuous Circle: This represents a positive feedback loop where heightened attention, mindfulness, and intrinsic motivations lead to positive outcomes such as creativity, self-esteem, and healthy curiosity. Scientifically, this aligns with theories of positive psychology, which emphasize the benefits of a positive mindset and proactive engagement with one’s environment.

-

Vicious Circle: On the other hand, negative inputs such as negativity, self-deprecation, and extrinsic motivations create a vicious cycle leading to apathy and dimmed awareness. This can be compared to cognitive-behavioral theories that describe how negative thinking patterns can lead to depression and other mental health issues.

Mindfulness and Cognitive Processing

-

Mindfulness: Mindfulness involves being present in the moment and observing one’s thoughts and surroundings without judgment. This practice enhances attention and helps filter out negative inputs, ensuring that the “ingredients” entering the factory are of high quality. Neuroscientific studies have shown that mindfulness practices can lead to structural changes in the brain, enhancing areas related to attention, emotion regulation, and self-awareness.

-

Intrinsic Motivation: When our actions are driven by intrinsic motivation, we are more likely to engage deeply and meaningfully with our tasks. This results in higher quality processing and better outputs. Research in motivation psychology highlights the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in fostering intrinsic motivation.

Practical Applications

To apply these concepts in everyday life, one can:

- Enhance Input Quality: Cultivate mindfulness, practice positive thinking, and seek enriching experiences.

- Refine Processing: Engage in activities that promote cognitive flexibility and emotional regulation, such as meditation and reflective practices.

- Improve Outputs: Foster environments that encourage creativity, learning, and self-expression, thereby reinforcing positive feedback loops.

By understanding and leveraging these principles, individuals can optimize their cognitive and emotional processing, leading to more fulfilling and effective lives.

Article:

Negative thinking is linked to dementia in later life, but you can learn to be more positive.

Are you a pessimist by nature, a “glass half empty” sort of person? That’s not good for your brain.